In Pureland Buddhism (Jodo in Japanese), Amida Buddha, a monk who reached Buddhahood and earned his own pureland through his merit, is seen as a kind, compassionate figure who invites all who chant: “Namu Amida Butsu” (Hail to the Amida Buddha) to live in his Western Paradise after they die. His is often portrayed in a Raigo (“Welcoming approach”) which is an image (painting or sculpture) of him descending to earth to welcome the souls to the Western paradise. At the Ho-o-do (Phoenix Hall), a part of what was once a villa of the Fujiwara clan near Kyoto, Japan, images adorn walls and a door, showing scenes of the Raigo. This building was constructed in the 1000’s during the Heian period (784-1183 CE). The text in the book Art Beyond the West describes the imagery: They include monks and bodhisattvas on clouds, and an orchestra-chorus of music-making and dancing Buddhist beings dramatizing the arrival of the Buddha. Together the many raigos, concentrated in this small, intimate space that was once a home, dramatize the compassion and glory of the Buddha in this popular sect of Buddhism (P. 164, Chapter 5). At the end of the film, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, however, the almost identical image is interpreted in a vastly different way. While Buddha appears both kind and compassionate, and his many attendants exhibit a beautiful, peaceful air, they are coming to take the title character, Kaguya back to the moon, from which she had previously left after hearing rumors of earth and the emotions living there evoke. Kaguya, who has spent almost a decade on earth (though she ages faster) has come to love it and it’s natural world and people. When she is being taken back to the moon, her adoptive parents, as well as many people she knew and some she didn’t watch her leave and express a grief at her going. She too had become desperate when she realized she would have to return, saying that she did not want to forget the earth and the places and people there, and the emotions they had inspired. This is a stark contrast to the emphasized joy and celebration of Pureland Buddhism and seems to question the idea that there should be a place of greater joy and beauty for us than the earth on which we are born, live our lives, and die. It also seems to suggest that if the earth is awe-inspiring and worthy of contemplation, as many Japanese practices say it is, then the it should not be abandoned in hope of finding greater understanding and happiness elsewhere.  While the film The Tale of Princess Kaguya does not have to be viewed in a scholarly or even analyzed way, such an approach does present some fascinating and helpful connections. For instance, the film is set in either the Heian (784-1183) or Kamakura (1185-1333) period, which for those of us with a bit of (art) history knowledge, will quickly become clear. However, one of the most important things about watching any Studio Ghibli film, and specifically this one, is to enjoy yourself a little, to laugh at the simple charming moment, or to just let the beauty and sorrows and longing and hope present in any of these films catch you up a little and let you see a new way to look at the world, a way that is both distinctly Japanese, and broadly human. -Bee

0 Comments

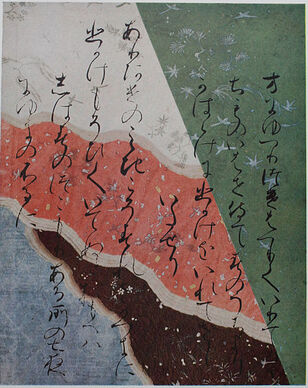

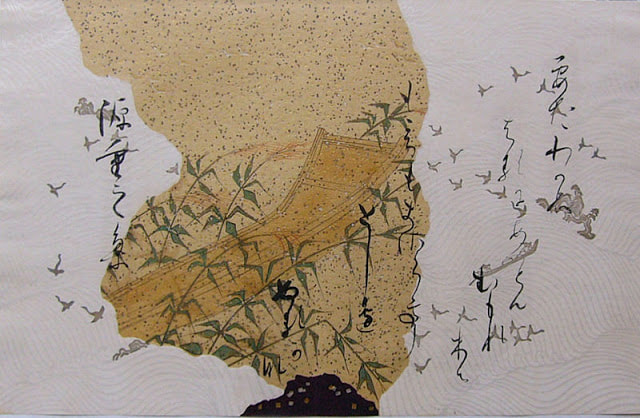

The film The Tale of the Princess Kaguya begins, in the manner of older western movies, and as many studio Ghibli movies do with the credits of filmmakers and cast over a unique background. However, for this film the animators noticed a chance to place the movie in a specific historical context and display the credits over a sheet of woodblock printed paper (See the image on the left). This kind of decorated paper was often used during the Heian period (784-1183 CE) for anthologies of poetry which had been beautifully rendered in calligraphy. This technique, called Chigiri-e involves handmade paper which is torn and aligned on other paper and additionally decorated with flecks of metallic dust or colored pigment. After completion, a calligrapher could write poetry over it, creating a beautiful, almost rustic look. As the textbook Art Beyond the West states:

two pages of the collected poems of Minamoto no Shigeyuki (?-ACE 1000), Artist Unknown

In these upcoming posts I will point out some particularly interesting parts of the film that tie into important aspects of Japanese aesthetics and techniques of art-makingOf all of the Japanese animation film studio, Studio Ghibli’s films, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is arguably the most rooted in Japan’s secular and religious history. Full of references to traditions in both artmaking and society, it not only celebrates Japanese religious and secular culture but also looks at and brings up important questions about certain less than perfect parts of that culture.  I also will address the broader philosophical ideas that shaped Japan’s culture, connecting these concepts from the film with quotes from the textbook Art Beyond the West by Michael Kampen O’Riley. The film Princess Kaguya is a visual masterpiece created appropriately in the popular Japanese anime style, an animation style which incorporates many historic Japanese illustration tendencies and traits of the past. This seemingly small yet incredibly effective choice for the movie, as well as the Studio's other films, makes it clear that this film’s intent is not just to look at and analyze the past but also to examine the present and elude to the future. While the movie may take on more complex meanings to those familiar with the artistic traditions and culture of Japan, Kaguya also lets those who have no such context appreciate and connect with the film and come away with new enlightening ideas about the world, life, and being human. I will begin by examining the Chigir-e torn paper artistic technique, then take a look at the Haboku (Broken Ink) painting technique, and finish with Pureland Buddhist imagery and philosophy. Together these different historic and cultural tie-ins will highlight some interesting aspects of the film, providing a fascinating context for The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. - Bee |

AuthorEach of the Silverfists take turns sharing their thoughts about illustration found in graphic novels, games, album art, and more... Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed